The Allied Counteroffensive: Breaking the German LinesAfter nearly four months of withstanding the might of the Kaiserschlacht, the German Spring Offensives, week after week after week, the Allied counterattack finally comes.

There was a lot of action far to the east in Siberia, but it was primarily a week of planning. The Germans finalized plans for their next Western Front Offensive, even in the face of a deadly flu epidemic.

That offensive, which would be known as the Second Battle of the Marne, kicked into gear this week.

German Plans for the Offensive

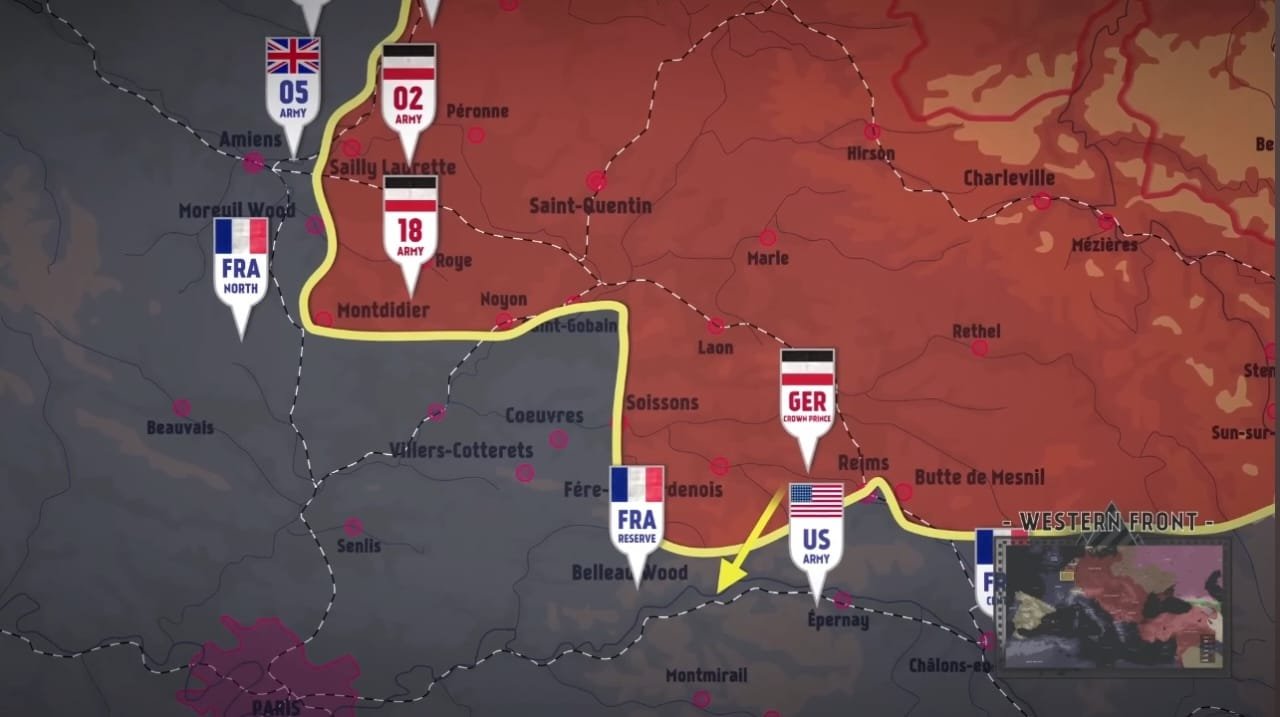

The Germans were going to attack with Crown Prince Wilhelm’s 49 divisions. One of the goals was to open a second railway line to the Marne, and also to draw off Allied reserves from Flanders in the north for an attack that would happen in just a few days.

French and American Defense

The Allies knew exactly when the attack was coming, so French and American artillery bombarded the German front lines and jumping-off points half an hour before the German bombardment began.

The German barrage was still strong, raining 17,500 rounds of gas on the sector of the front held by the American Rainbow Division. Then the Germans went over the top east of Reims and found that the French trenches weren’t exactly trenches. They were lightly manned, and the German bombardment had been wasted on them. The Germans overran these and killed what few defenders there were, but the real trenches further back were basically untouched and full of French soldiers.

French General Philippe Petain, after pushing for so long for the French to use a defense-in-depth system to neutralize the German shock troop advantage, had finally gotten his wish. General Henri Gouraud had implemented it, and as the Germans advanced on the manned trenches, they came under heavy fire from French and American artillery. The Chief of Staff of the Rainbow Division, Douglas MacArthur, noted, “When they met the dikes of our real line, they were exhausted, uncoordinated, and scattered, incapable of going on without being reorganized and reinforced.”

That was east of Reims. West of Reims, where the French under Jean Degoutte and the French and Italians under Henri Berthelot were using the old system with the men too far forward, the Germans were quickly successful. However, their failure in the east meant those successful troops were dangerously exposed, so they called off the attack in the west. But the attack had to continue somewhere, as it was essential to draw Allied reserves away from Flanders before the German attack up there.

The Battle in Champagne and the Rock of the Marne

On the 16th, the German bombardment was renewed, now against the French and Americans in Champagne, including half a million gas shells. Over the next two days, it seemed the Germans would break through, and that could have been the decisive breakthrough. However, in one sector, French gunners knocked out all 20 German tanks. In another, fewer than 4,000 Americans, outnumbered three to one, held their ground in vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Overhead, 225 French bombers dropped 40 tons of bombs on the bridges the Germans had set up across the River Marne.

Near Chateau-Thierry, the American 3rd Division blew up every single pontoon bridge the Germans had set up in the whole sector, earning itself the name “the Rock of the Marne.” But the Germans kept on coming, pouring into the river in the face of machine guns and infantry. By noon that day, as American General Joseph T. Dickman wrote, “There were no Germans in the foreground of the Third Division except the dead.” The Americans also took heavy casualties holding back the tide.

On the 17th, Italian troops stopped the Germans at Nanteuil-Pourcy.

The Turning Point: Allied Counterattack

On the morning of the 18th, German Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff had a conference with his command, dismissing any possibility of an Allied counterattack in the south. However, around noon, word came that Allied Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch had, in fact, launched an Allied counterattack.

It kicked off with a 2,000-gun artillery barrage along just over a 40km front. French General Charles Mangin led 23 divisions—four of them American—following nearly 500 tanks in an attack to try and recapture Soissons and seal off the German salient. The Germans were wholly surprised. Part of the reason was overconfidence: Crown Prince Wilhelm had thought the Allies were too weak to defend Reims and counterattack.

The Allies agreed that surprise was crucial for success, so they concentrated the forces leading up to the attack in just four days—nights, actually—since it was all done in darkness, and the tanks were hidden in the forest. This counterattack was huge, on a front of over 100km by four armies, but the spearhead was the 1st and 2nd American Divisions and the 1st Moroccan Division.

Breaking the German Lines

The bulk of the tanks were light Renaults, armed with machine guns, that could go around 13-14 km/hour, and they attacked out of the mist. The German lines broke, and they were driven back some 7km, with 20,000 Germans taken prisoner, along with 400 big guns.

As the week ended, Mangin was stopped before reaching Soissons, and there were heavy Allied casualties—such as the Italian Corps losing a third of its strength. But after just the first two days, the Germans might have no realistic hope left of taking Reims, and the German threat to Paris would be no more. More importantly, if the Marne salient became unholdable, Ludendorff would have no choice but to postpone the Flanders offensive indefinitely.

Key Moments and Tactics

There is a story from this week, perhaps true, of a ruse devised by a couple of American engineers. A briefcase with fake plans for the counterattack was handcuffed to a man who had died of pneumonia. They placed him in a vehicle that looked like it had run off the road at a German-controlled bridge. The Germans found the plans, believed them, and adjusted their own plans to stop the fake Allied plan. When the real Allied attack came, it hit an exposed part of the German lines, forcing them to retreat.

On the 16th, German Flying Ace Hermann Göring shot down his 22nd plane. Three days earlier, he had taken command of the Richthofen Squadron, named after Baron von Richthofen, the Red Baron, who had been killed in April.

Other Fronts of the War

There was action on other fronts this week as well. On July 13th, using mainly German troops, General Liman von Sanders attacked British General Edmund Allenby’s bridgehead on the east bank of the Jordan River, northeast of Jericho. However, Australian troops pushed back the attackers.

In the Caucasus, Nuri Pasha’s Army of Islam advanced at a crawl toward Baku.

Summer heat, lack of drinking water, poor supply lines, and an epidemic of dysentery slowed his army, leaving only 4,000 fit for combat by the time they reached Kurdamir. Add to that the Azeri militia were deserting in droves, so he had only around 8,000 men at the moment available to try and take Baku and its oilfields. But he would try at the end of the month.

On July 16th, 1918, Tsar Nicholas Romanov and his family were executed at Yekaterinburg, capital of Red Ural, by order of the Ural Regional Soviet. Deposed by the February Revolution last year, Nicholas had been the force that guided Russia into this war four years ago.

There was also news this week from another initial guiding force of the war; on July 15th, after the huge failure of the July Austrian offensive in Italy, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf is dismissed and placed on the retired list. He is also raised from Freiherr to Graf, so like from Baron to Count, but for Conrad this war is over.

And this week of the war ends, with yet another German offensive, but a mighty Allied counterattack that, as the week ends, is a success. A German failure in the Middle East, setbacks in the Caucasus, and the death of a Tsar. Well, he was no longer the Tsar.

Historical Context: Leadership and Legacy

When you think about it, there’s nearly no one left. The leaders – the men who guided the world into this war or led the armies, or both, 3 years and 50 weeks ago – they’re almost all gone. Call the roll: Nicholas, Conrad, Franz Josef, Moltke, Joffre, French, Putnik – they’re all gone. Only Enver Pasha and Kaiser Wilhelm remain at their posts from those 1914 days, and even the Kaiser’s power has been reduced by army command.

It’s now different men, fighting with different weapons and different tactics, and it’s also a totally, totally different world.